The Intriguing Origins of Mother’s Day

Mother’s Day is generally perceived as a sweet, albeit mundane occasion. Think flowers, heartfelt cards, and perhaps a rare act of tidying up around the house. However, the American iteration of Mother’s Day is not merely a product of lush gardens. It was shaped in the turmoil and tragedy of the Civil War, molded by fierce women, and transformed into a battleground between ethics and commerce—a celebration so fraught that its very founder dedicated her life to dismantling it. The narrative surrounding Mother’s Day is as captivating as it is complex.

The Historical Roots of Mother’s Day

The concept of honoring mothers is ancient, with roots tracing back to various cultures. The Greeks and Romans revered motherhood through festivals dedicated to deities like Cybele and Rhea. In the Medieval era, the church added a Christian dimension with the observance of Mothering Sunday, which celebrated the ‘Mother Church.’ Different countries around the globe have their own ways to recognize mothers; for instance, in Peru, families visit graveyards on this occasion, while in Albania, it’s celebrated on March 8. Yet, these global variants did not directly influence the Mother’s Day we recognize in the United States today.

A Holiday Forged in Conflict

The official recognition of Mother’s Day in the U.S. occurred in 1914, but its roots delve deeper into the Civil War era, emerging from the efforts of social advocate Ann Reeves Jarvis. Known as “Mother Jarvis,” she was a pioneer of Mothers’ Day Work Clubs, which aimed to reduce infant mortality rates by equipping women with knowledge on caring for their children and improving sanitary conditions. This mission was deeply personal for her, having lost most of her 11 to 13 children before they reached adulthood.

As the Civil War erupted in 1861, these clubs pivoted their focus to support soldiers from both the Union and Confederacy. With the war’s end, Jarvis championed a peace movement called “Mothers’ Friendship Day,” aimed at reconciling former soldiers.

“Why do not the mothers of mankind interfere in these matters to prevent the waste of that human life of which they alone bear and know the cost?” Jarvis remarked, urging mothers to take a stand.

Other women across the nation were similarly engaged in advocating for maternal-themed events. Influential figures like abolitionist and suffragette Julia Ward Howe wrote the “Mother’s Day Proclamation” in 1870, urging mothers to unite for global peace. Howe later called for a holiday titled “Mother’s Peace Day” to be observed every June 2. In the 1870s, Juliet Calhoun Blakely, a temperance activist from Michigan, inspired a local observance of Mother’s Day, signaling the cultural shift towards recognizing mothers, although it ultimately was not until after Jarvis’ passing that it gained formal status.

Commercialization Takes Over Mother’s Day

Ann Reeves Jarvis passed away in 1905, but her daughter, Anna Jarvis, continued the fight. On the first anniversary of her mother’s death, she initiated plans for a memorial service to be held the next year, envisioning a national holiday to acknowledge the sacrifices mothers make. In 1908, supported by prominent figures like John Wanamaker and H.J. Heinz, she organized official Mother’s Day celebrations in West Virginia and at Wanamaker’s department store, further catalyzing the call for a national holiday. However, this also sparked interest among entrepreneurs, revealing the commercial potential of Mother’s Day and igniting a struggle for its essence.

By 1912, Jarvis had resigned from her job to establish the Mother’s Day International Association, forming alliances with local enterprises and launching campaigns to engage government officials. Towns and religious institutions in various states began yearly celebrations of Mother’s Day, which culminated in President Woodrow Wilson officially designating it a national holiday in 1914. While detractors like Senator Henry Moore Teller criticized the resolution, it was widely embraced by the public.

Yet, instead of retaining its heartfelt sentiment, the holiday quickly morphed into a marketing opportunity. Jarvis envisioned Mother’s Day as a time for genuine emotion, not commercial profit, but business moguls ignored her pleas, transforming the day into a consumerist extravaganza.

Jarvis’s Quixotic Battle Against Commercialization

By 1920, Jarvis openly condemned her former allies, urging everyone to refrain from purchasing gifts for their mothers and denounced anyone who profited from the holiday as “charlatans, bandits, pirates, racketeers, kidnappers, and termites” undermining a noble cause.

She protested against restaurants promoting Mother’s Day specials by dramatically spilling a “Mother’s Day Salad” on the floor of a Philadelphia establishment. Jarvis also criticized greeting cards as insincere, stating, “A maudlin, insincere printed card or ready-made telegram means nothing except that you’re too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone else in the world.” Additionally, she admonished the gift of candies, quipping that it merely served to let the giver indulge in the treat themselves.

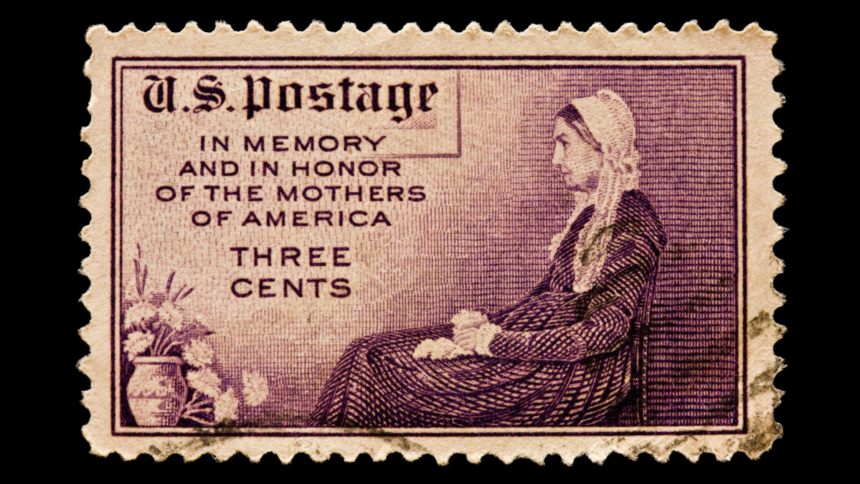

The floriculture industry became her primary target; Jarvis harbored a profound disdain for florists. She invested her own resources in sending buttons featuring a white carnation, the symbol of Mother’s Day, to groups nationwide, requesting them to boycott floral purchases. She even threatened legal action against Florist Telegraph Delivery for using “Mother’s Day” in conjunction with carnations. Jarvis expressed her displeasure when the U.S. government issued a Mother’s Day stamp featuring a painting of Whistler’s Mother, interpreting it as advertising for the floriculture business. Her protests became so fervent that she was arrested for disturbing the peace while attempting to halt the sale of the flowers.

The Tragic Demise of the Founder of Mother’s Day

Ann Jarvis remained unwavering in her convictions, calling out the profiteers of her own holiday. As the years passed, her financial situation deteriorated dramatically. By the mid-20th century, she found herself destitute, residing in her sister’s home in Philadelphia, far removed from the influence she once exerted. In 1943, while gathering signatures for a petition to abolish Mother’s Day, she was committed to Marshall Square Sanitarium, where a representative from the flower and greeting card industries paid for her care, leading to speculation about the motives behind their assistance.

Jarvis passed away on November 24, 1948, having never had children but remaining steadfast in her principles, even in death. Her legacy is a poignant reminder of the holiday’s tumultuous evolution from a day of honoring motherhood to one of rampant commercialization.